India’s Current NPA Mountain: Result of Absence of Institutional Learning

Deep N Mukherjee Download ArticleIndia has been There Before

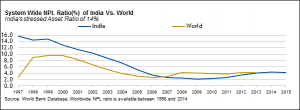

Last time it took 9 Years: In 1997, India’s banking system’s Non-Performing Loans to Total Gross Loans (NPLTGL) was 15.7 %( Source: World Bank). It took 9 years for the NPLTGL ratio (domestically referred as NPA ratio) to fall below 5 %( 3.2% in 2006). Between 1997 and 2002, the growth rate of Nominal GDP was 4.4%, real interest rate averaged at 7.7% and the NGLPTL reached 8.8% by 2002. Between 2002 and 2006 the nominal GDP of India grew at a rate of 16%, while during the period the real interest rate averaged 5.7%.

Here it must be highlighted that since the loan and NPL are nominal (not adjusted for inflation) the nominal GDP trajectory is more important than the real GDP.

Nominal GDP and Real Interest Rate: If an economy enters into a deflation mode (i.e.; systemic inflation becomes negative) then nominal GDP growth becomes lower than real GDP growth. Economy observers focussing only on real GDP, in such situations, may draw a dangerously incorrect conclusion that the economy is recovering and the economy’s bad debt problem would get resolved. But in practise the opposite happens.

Corporate Earnings (which are of course nominal) tends to come down and more companies find it difficult to service their debt. Thus the NPL (or Non-Performing Assets (NPA) as is often referred in India) actually worsens. While, the attractiveness of prevailing interest rate to business is driven by the real interest rate ie; lending rates adjusted for systemic inflation -The measure often used is GDP Deflator. To illustrate, at the cost of over simplification, if the nominal (prevailing) lending rates are 11% and the inflation is 10%, businesses would expect their revenues and earnings to grow at a brisk pace without presenting much challenge to service debt at an interest rate of 11%. However, if prevailing lending rates are 9% and the systemic inflation is 2%, most businesses would expect their revenue and earnings to grow at low single digit growth rates. They might not find the 9% rate of interest very enticing. However, in popular discourse some experts often focus on exactly the opposite. The focus on real GDP and nominal interest rate!

Almost back to 1997: The formally recognised NPA rate as of 30th September, 2015 was slightly above 5%. However, Mr. S.S.Mundra , Deputy Governor of RBI stated, at a banking summit organised by Confederation of Indian Industries(CII), that as of 30 September,2015 the amount of Gross NPA plus restructured loans plus written off loans stood at 14% of the Indian banking assets. And this may go up further by 31st March,2017 which is the deadline that RBI has set for Indian banks to ‘clean-up’ their books.

With nominal GDP growth hovering at sub 10% level(FYE16:8.6%) and real interest rate at around 7%, one may be forgiven for wondering if it would take a good six to nine years for the current the NPA rates to come down if the previous century’s experience is repeated. But one can always hope that things may not be that bad as they say ‘this time it will be different’.

The ‘NPA Cycle’

An Economic Event: In general bankruptcy/defaults are economic events. It is generally observed in most countries that system wide NPA rates rises when the economic growth moderates and NPA rates starts to fall when the economy revives. The worldwide NPLTGL ratio in recent decades peaked around 2000 (9.65%) and 2001(9.6%). Global economic activity revived post 2002. The global nominal GDP growth rate between 2002 and 2008 was 10.6%. The NPLTGL rate improved and reached its lowest level in 2007(2.7%). Of course it started creeping up and started hovering around 4%, where it remained till the most recent year of available data (2014) in the World Bank Database.

Here the point to be highlighted is that despite the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, arguably one of the worst economic shocks post World War II, the global NPLTGL has not jumped back to 8%-9% level.

Of course one may argue that the problem of timely identification of default is not limited to India and the NPLTGL at a global level may be higher than the 4.23% reported in 2014. Still this is not even half of the peak NPLTGL levels seen in 2000. Given bulk of the banking assets are in North America and Eurozone, where default identification mechanism is relatively more robust than in emerging markets such as India, even after possible future adjustment the global NPLTGL number is unlikely to come close to 9%. Though it can be higher than 4.23%. However, in India the stressed asset rate is already 14% of banking sector assets and in all probability can move higher.

Questions Maturity of India’s Risk Management Practises: The retracement of systemic stressed assets levels at present to levels comparable to 1997-98 may suggest that the current NPA issues in India are not entirely due to pure economic cycles. Extra-economic factors had a huge role to play. The other doubt that may be raised is whether the Indian banking system had learned and remembered the lessons of the past. Has the improvement in the level of sophistication of Indian banking’s credit risk management systems, kept pace with the growing complexity of Indian economy and Indian corporates?

Previously, the NPA rate fell because economic growth shot up between 2002 and 2006. Likewise the fall in real interest rate also provided the necessary support to credit lead investment growth. Thus the fall in NPA rate till 2006 had a lot to do with the rise in the denominator (total banking system assets) and to a lesser extent on reduction in numerator (absolute level of Gross NPA). Under such circumstances it is possible that the learnings of risk management in Indian banking system has not been as widespread as one would have preferred.

However, the world economy is replete with examples of countries who faced high levels of stressed assets in 1990 and early 2000, but have learned their lessons well. Thus we see for a lot of these countries, the NPA rate (or NPLTGL for that country) has not shot up significantly post 2008.

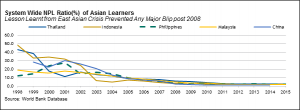

Systemic Bad Debt Problem not uncommon: During the period 1997 to 2001 several countries had bad assets which were well over one-fifth of their total banking sector assets. Notable among them are Indonesia (1998:48.6%), Thailand (1998:42.9%), China (2001:29.8%), and Turkey (2001:29.3%). However, each of these country’s banking sector had taken the lessons to heart. So in the aftermath of GFC the impact on the banking sector’s stressed asset rate had been in check. While in India the stressed asset rate has kept on increasing since 2011 and is closing in to 1997 levels without showing any signs of a reversal at least over the next few quarters.

I have focussed on 34 prominent economies and studied the behaviour of their respective banking sector’s NPL/NPA rate. These 34 countries were divided into five categories:

- Most Steady Hands in Business b)Steady Hands with Minor Hiccups c) Learners d)Slow Learners e) New Students

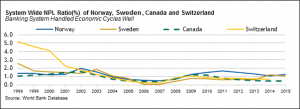

Most Steady Hands in Business: Even among developed countries one may easily benchmark countries such as Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and Canada against others. These four countries have kept their systemic NPL rate in check over last two decades. To their credit, even post 2008 GFC, the incremental deterioration in their stressed asset ratio was unexceptional. While Norway, Sweden and Canada had consistently low systemic NPL rates, Switzerland has been a sharp learner as may be indicated by only a small spike in NPA rate in 2009 which of course was checked by 2011.

As per World Bank report during the period (2004 to 2014) the average days required for contract enforcement improved from 508 days to 314 days for Sweden and for Switzerland it improved from 417 to 390 days. With the exception of Switzerland (~45%) the other three countries had recovery rate in excess of 75%.

Given the maturity of their banking and systems, this controlled NPL rate across economic cycle as well as in response to economic shocks may not have been surprising.

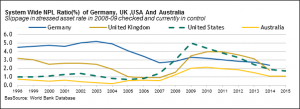

Steady Hands with Minor Hiccups: Next would be countries such as Germany, UK, USA and Australia. Over two decades their systemic NPA rates has been in control, however there was significant slippage in 2008-09. USA which was in the epicentre of GFC as well as UK which had a high exposure to US economy showed the highest relative deterioration in stressed asset rate. However over the next six years despite very moderate economic growth the systemic NPL rate came down close to historical average. Of course apart from structurally advanced credit infrastructure the near –zero interest rate and quantitative easing also played their part to boost corporate earnings and reduce NPL rate

Learners: The previous two groups consisted essentially of developed nations with well-established institutions and highly evolved and efficient legal infrastructure. However, the learners essentially consist of emerging nations who have learned their lessons and were able to check the system-wide NPL rate post 2008. However, one should be cautious before singing praises for all these emerging market learners for two reasons. First, at least some of them have issues in prompt identification of distressed asset on similar lines as India. Second, a lot of them are heavily dependent on commodity prices or exports and the last word is yet to be said on their NPL rates. Still one thing that may be noted is that even if their NPL rate goes up post 2015, they are unlikely to come even close to the levels observed in late 1990s or early 2000.

One should of course separately mention Singapore and Japan. Post 2008 both these countries had very low to negative GDP growth but still there was no spike in their NPL rates.

Among Emerging markets the best learners are South Africa and Turkey. The blip they showed in their respective systemic NPL rate in 2009 were very insignificant and they were corrected in the next 1-2 years. Of Course South Africa is facing a tremendous challenge on its economic front and it will be worthwhile to observe how high the NPL rate goes.

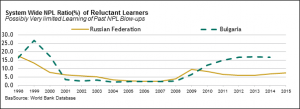

Slow/Reluctant Learners: India may have well been part of this group along with Russia and Bulgaria, where NPL rates came down during period of economic boom and shows signs of shooting back to historically high NPL rate levels.

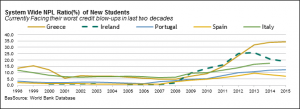

New Students: These are mostly Eurozone countries. These are currently having systemic NPL rates way above what they have experienced in the last two decades. Some of them such as Spain have a history of coming out of such crisis. While the problem has been a direct outcome of low economic activity which was a result of fiscal austerity in most instances, still the steps these countries may be taking may have important pointers for India.

The Indian Situation

In India the present system is banking on the enactment of the bankruptcy code into law to help the current NPA situation. However, as the latest Companies Act related uncertainties suggests, passage of the bill in the Parliament is only the first step. Equally critical is the notifications of the law which would come up from the ministry. This can take anywhere between six to 24 months if not more. And assuming that the notifications which are the implementation details of the enacted law are reasonably unambiguous, the doubts continue as to how the country’s overburdened legal system would handle this extra burden. In all likelihood India’s current NPA crisis is yet to reach its peak and even if the bankruptcy code is enacted it will not provide any immediate help.

Besides one question that repeatedly gets pushed below the carpet is whether the banking system as a whole have sufficient knowledge and sophistication in the credit risk management sphere? Are they able to handle the complexity of the large Indian conglomerate? Do they have the requisite skills and bandwidth to look through the accounting numbers of Indian balance sheet, with some of them having possible forensic issues? It will be a surprise if the answer is yes.

*******