Deleveraging Balance Sheet

Ashok Banerjee Download ArticleLeverage in the balance sheet increases financial risks resulting in lower credit rating and higher cost of funds. A healthy mix of debt and equity is key to debt sustainability. Too much debt increases the marginal cost of borrowing due to expected distress cost and also cost of equity via higher levered beta. Therefore, corporate finance theories suggest that there is limit to borrowing. Traditionally corporate India borrowed from banks for both short term and long term requirements. Any corporate loan default adversely affects the balance sheet of a bank. Debt default is not always deliberate. Leverage has side benefits too: one, tax shield on borrowing and second, debt, it is said, disciplines management. The benefit of tax shield is immediate for those firms, which make operating profits. An all-equity company will not have any pressure of contractual obligations for timely interest payment and loan repayment. Replacing equity with debt (e.g., share repurchase) puts more pressure on the management to perform as the firm swaps promise (dividend) with obligation (interest). Highly indebted firms face difficulty in negotiating favourable terms with suppliers and even customers put pressure to squeeze extra credit period.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), while sympathetic to corporate defaults due to uncontrollable extraneous factors, has come very hard on wilful defaulters by threatening to ‘name and shame’ such borrowers. RBI has, over the past two years, brought several schemes to help stressed borrowers to restructure their debt and at the same time allowed lending banks to change promoters of wilful defaulters. Three companies in India together owed more than Rs. 3 lakh crores (US$46 billion) to banks at the end of March 2015. If one takes the top ten indebted companies in India, the figure goes up to Rs. 7.3 lakh crore (more than US$100 billion) for the same period. This alarming proportion of debt puts tremendous strain on the balance sheet of banks.

The main issue, therefore, is to explore how leverage affects a firm, a bank and ultimately a nation. Myers(1977)[1] demonstrated that the outstanding level of debt in a corporate balance sheet can alter the investment decisions of firms. Firms with higher debt will underinvest by not accepting many positive NPV (net present value) projects in pursuit of higher return, as those projects would not leave anything for the shareholders after paying for debt. Typically, bank debts are collateralised on the assets of firms and hence during recession when the market value of assets fall, such firms face structural bankruptcy in the balance sheet. Such apparent bankruptcy threats make firms more conservative with investment. In other words, during economic boom, rising firm income and asset prices boost borrowing and opposite happens during economic bust. This is known as procyclical feature of leverage. Debt overhang in a bank arises when the scale of debt relative to the value of assets distorts lending decisions. At a macro level, leverage is defined by the debt-to-GDP ratio. A nation with higher leverage would face restricted investments, which in turn may adversely affect potential output growth. Therefore, too much debt is bad for everybody and the recent recession in 2008 confirmed this hypothesis. Globally one can observe increasing trend in deleveraging balance sheet, particularly post-recession.

Effect of Deleveraging

Broadly, firms can reduce debt on the balance sheet in two ways- (a) raising equity and (b) disposing assets. A famous example would be that of BP. After the Gulf oil spill, BP sold billions of dollars in assets and used that cash to pay hefty fines and shore up cash reserves. Deleveraging with equity infusion may be the best course of action for companies that have become over-levered and are flirting with financial distress. Merrill Lynch (now known as Bank of America Merrill Lynch) regularly conducts fund manager and CFO surveys. In one of such surveys conducted in 2002 (much before the global financial crisis), majority (54%) of respondents said that they prefer repayment of debt as the best use of free cash and the consensus reached 62% in 2003. The same trend is observed post-crisis. In a recent survey on Asia in 2015, CFOs (51%) mentioned that deleveraging is the main motive for change in capital structure.

If debt is cut with fresh equity, the capital structure adjustment may reduce cost of capital. But it does not help in future growth of the company. More damaging is the case when assets are disposed to pay down debt (Table 1). This strategy reduces the overall balance sheet size and hence shrinks output. If majority of firms follow this practice, it would seriously affect economic growth of a country. Thus, deleveraging is good to reduce financial risk. But if higher leverage makes a firm risk averse, the firm would tend to use free cash to reduce debt rather than invest in positive NPV projects. Countries with higher debt-to-GDP ratio may also suffer from the same underinvestment problem.

Burden of financial debt typically leads to cut in capital expenditure and even disposal of assets to bring down debt. This strategy may help a firm in the short-run. However, if this practice is sustained for long it would lead to massive underinvestment hurting economic growth. Tendency to hoard cash would generate suboptimal returns leaving shareholders poorer. Data released for British firms in 2012 showed that, since mid- 2008, firms have cut more debt than they have raised equity.

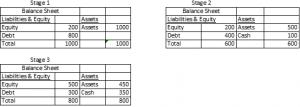

Table 1: Impact of deleveraging

The hypothetical firm (Table 1) was highly levered in Stage 1 and had to significantly dispose of assets to reduce debt (Stage 2). This deleveraging was necessary to improve the financial health of the balance sheet and thereby corporate rating. But in the next stage (Stage 3), the firm gets conservative and starts hoarding cash. Revenue earning assets of the company shrunk by more than 50%; leading to underinvestment problem. The excess cash is generally invested in government bonds, bank deposits or mutual funds, which earn suboptimal return. As firms stop investing, banks that get such corporate deposits also do not find borrowers. Banks again put this money mostly in government bonds. If the country already has higher debt-to-GDP ratio, it also does not invest. Thus the consequence of leverage cycle is lower future economic growth. It is not good to have high leverage on the balance sheet. It is equally bad to hoard cash and underinvest.

This trend can be seen in Indian corporate sector. A report[1] shows that companies and banks in India are sitting on cash piles (Table 2). The four banks hold about Rs. 400,000 crores (USD 61 billion) in cash. Thus, corporate deleveraging exercise is ultimately fuelling cash hoarding.

Table 2: Cash Holdings

| Company | Cash & Bank (% of Total Liabilities) |

| Rajesh Exports | 150.51 |

| GSK | 110.90 |

| MRPL | 103.54 |

| Novartis India | 95.79 |

| Bharat Electric | 83.89 |

| Bank of India | 20.67 |

| PNB | 11.31 |

| Canara Bank | 10.54 |

| SBI | 7.98 |

Cash Hoarding

Hoarding cash has become a popular practice for corporate sector. Top ten US companies held more than $675 billion in cash by the end of 2015[2]. Cash-rich companies in India have decided to use the cash for share buyback rather than investing in new projects. This trend is seen globally too. The Merrill Lynch survey showed that approximately two-thirds or more of all U.S. companies say they intend to hold constant the percentage of free cash flow they allocate to share repurchases (77 percent), dividends (76 percent), research and development (67 percent), and acquisitions (66 percent). The problem is that the cash so distributed by firms do not reveal itself in investment and employment. It rather shows up in savings. Firms with huge cash balance have negative debt and such a situation is not tax efficient.

Situation in India

Like other countries, India too had launched generous financial stimulus to help corporate sector fight recession. RBI reduced interest rates significantly to offset the increase in private sector risk premium and to underpin aggregate demand. In spite of these efforts credit remained tight-banks were hesitant to lend immediately after recession leading to weak aggregate demand. Table 3 shows leverage situation of three select cement companies in three different economic regime.

Table 3: Leverage-Growth nexus[3]

| Company Name | Year | Liquidity | 5-year Sales CAGR | Leverage | Asset Build up |

| A C C LTD. | 2005 | 1.81% | 8.02% | 35.44% | 73.18% |

| A C C LTD. | 2010 | 8.20% | 18.25% | 8.64% | 41.91% |

| A C C LTD. | 2015 | 9.56% | 8.97% | 5.92% | 79.68% |

| AMBUJA CEMENTS LTD. | 2005 | 3.40% | 18.36% | 37.24% | 26.71% |

| AMBUJA CEMENTS LTD. | 2010 | 15.87% | 22.40% | 6.37% | 43.66% |

| AMBUJA CEMENTS LTD. | 2015 | 20.04% | 5.27% | 5.55% | 38.22% |

| ULTRATECH CEMENT LTD. | 2005 | 1.55% | NA | 58.53% | 20.40% |

| ULTRATECH CEMENT LTD. | 2010 | 1.12% | 20.38% | 29.39% | 17.44% |

| ULTRATECH CEMENT LTD. | 2015 | 0.79% | 27.49% | 22.28% | 62.89% |

Note: Liquidity= Cash & cash equivalents (% Assets), Leverage = Long-term debt (% Assets) and Asset Build up= Capex (% operating cash)

Generally, companies have reduced leverage post global crisis. Such deleveraging exercise has somewhat adversely affected the top line growth of the companies. Companies were also careful in adding physical capacity. The cement industry had severely curtailed its spending immediately after 2008 economic crisis; reduced its debt and built up liquidity in 2010. In next five years, this sector has again witnessed investments in physical capacity. However, interestingly deleveraging continued. This is mainly due to cyclicality of the industry with general economic growth. So favourable operating cash helped these firms to maintain growth with lower leverage. Indian firms seem to negate the global story that deleveraging also reduces capital expenditure. At least the top three cement companies seem to spend substantial part of operating cash for growth and debt reduction.

[1] http://www.moneycontrol.com/stocks/marketinfo/cashbank/bse/index.html

[2] A recent Financial Times report states that US companies’ cash pile hit $1.7 trillion.

[3] Computations done by Mr. Bobbur Abhilash Chowdary, a fourth year FP (PhD) student at IIM Calcutta. Data source: Prowess

*************