Non-Performing Assets of Indian Public Sector Banks: Is all Well?

Partha Ray Download ArticleThe Financial Stability Report of June 2016, recently released by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is an interesting reading. Notwithstanding the standard Central Bank Speak, often couched in terms of what is known as ‘constructive ambiguity’, the report reveals some serious concerns on Indian banking – the most important being the state of non-performing assets (NPAs) of the Indian public sector banks.

The report confirms the already known fact that not all is well in the health of Indian banks. In fact, the gross NPAs rose sharply to 7.6 per cent (of gross advances) in March 2016 – this is 250 basis points increase over the last six months – from 5.1 per cent in September 2015. But this is only part of the story – if one adds the quantum of restructured assets to NPAs, then the overall “stressed advances” rose to 11.5 per cent in March 2016. Stripped of jargon, in simple terms, it reveals that more than 10 per cent of the loans extended by banks in India are bad debt.

Trends in NPAs

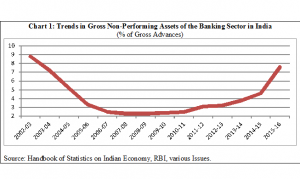

But was this expected? In fact, if one looks at the intertemporal behaviour of NPAs of banks in India since 2002-03, numbers show remarkable improvements till about 2009. Since then the NPA situation started deteriorating, so much so that by March 2016, it appears that all the progress achieved during the last one decade or so, has evaporated and Indian banks in 2016 are back to the situation prevailing in 2002 (Chart 1)!

Chart 1: Trends in Gross Non-Performing Assets of the Banking Sector in India

(% of Gross Advances)

Source: Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy, RBI, various Issues.

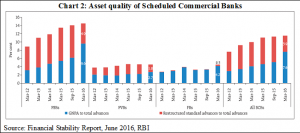

But this deteriaration is not uniform across all banks. There is great difference in the extent of formation of NPA across ownership-specific bank-groups. Effetively, the derioration in NPA front is primarily driven by the public sector banks; in recent times, the NPAs of private banks are less than one-third than those of public banks (Chart 2). Since the issue is primarily related to the public sector banks, one can go a step further and add that it is beyond the financial sector in India and that it becomes effectively a fiscal risk, imposing a burden on the already stressed State Exchequer.

Chart 2: Asset quality of Scheduled Commercial Banks

Source: Financial Stability Report, June 2016, RBI

To release or Not to Release (the names of big defaulters)?

Who are responsible behind such deterioration? Have the banks become more inefficient in recent times? Or, are bank borrowers, of late, going through bad times? Is it effectively a cyclical phenomenon? Such questions are raised. In popular discourse the situation is often seen as a product of Indian variety crony capitalism whereby a coalition of bankers-bureaucrats-politicians-corporates could have generated this unwanted outcome. In fact, there is a larger debate about the desirability (or its lack) of revealing the firm-specific or indutry house-specific data on bad debt. Like any major issue in public policy, in this case too, arguments exist on both sides. Illustratively, in a country where farmers routinely commit suicide on account of debt burden, one can legitimately question the lack of enthusiasm of the authorities to publish such data; at the same time one can also be sceptical about the lack of investigative journalism in this regard. On the other hand, it can be argued that when a particular business venture of a business house goes through a bad patch, leading to its inability to pay back bank loans because of some legitimate and secular reasons, publishing such price sensitive information could be a recipe for an overall corporate disaster. After all, historically, the notion of limited liability came up with the motive of ring-fencing one’s personal property from the assets of a company.

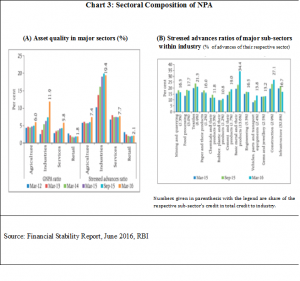

Sectoral Composition

Leaving aside such an issue, in absence of any firm data of industry-group-wise contribution to NPAs, one can only look at some collaborative evidence. What we now know is that small firms or priority sector advances are not responsible behind the NPA mess; and thus, unlike many of our economic malaises, the NPA situation is not an outcome of macroeconomic populism. In fact, bulk of the NPAs have emanated from the industrial sector, in which share of construction, basic metals, infrastructure, and textiles are rather large (Chart 3).

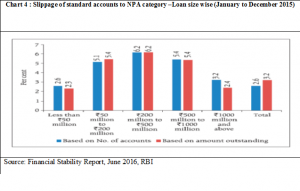

In fact, in terms of size class, much of NPAs that sprang during 2015 are concerntrated in the size of Rs 200 million to Rs. 500 million (Chart 4). Apart from the possibility of crony capitalism and laxity on the part of the bankers, several factors seem to be responsbile behind such a phenomenon.[1] First, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the regulatory foreberance adpted by the Indian authorities could have been too aggressive.[2] Second, in some of the sectors like steel and basic matels the story is part of the global recession and consequent nose-diving of metal demand. Third, in its over-zealous pursuit of infrastircuture projects under the PPP model, both the government / banks as well as corporates could have kept the old-fashioned calculations of project viability under the carpet. Finally, in general many of the Indian corporates have taken the easy route of debt financing; this is refleted in a 2015 Credit Suisse Report on India that noted a seven-fold increase of indebtedness of ten heavily indebted Indian corporates over the last eight years.

Recent Initiatives

However, not all is lost. Some efforts to ease the situation are already under way. The RBI has issued guidelines on a ‘Scheme for Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets’ (S4A) on June 13, 2016. The S4A scheme “envisages determination of the sustainable debt level for a stressed borrower, and bifurcation of the outstanding debt into sustainable debt and equity/quasi-equity instruments which are expected to provide upside to the lenders when the borrower turns around”.[3] The Scheme has been criticized on the ground that promoters are not brining any assets. In fact, in a recent interview, the RBI Deputy Governor S S Mundra went on to say:

“… These are not the best solutions; these are the second-best solutions. We don’t have the best solution in place at this point. Hopefully, it will be put in place. once it comes (Bankruptcy Law), things will be dealt with under that structure. It leaves room for a potential upside and when that comes, the one who has sacrificed more should also gain more.”[4]

As part of its Indradhanush Proposal of April 2015, Government of India has earlier proposed revamping the public sector banks by infusing capital worth of Rs.70,000 crores out of budgetary allocations for four years – for Rs 25,000 crore in 2015 -16; Rs. 25,000 crore in 2016-17; and Rs 10,000 crore in each of 2017-18 and 2018-19.[5] During 2015-16, 21 public sectors banks got fund support of Rs 25,000 crore; of this, SBI got the highest amount of Rs 5,393 crore followed by Bank of India at Rs 2,455 crore. More recently, the Finance Minister reiterated the government’s intention to stick to the declared schedule of capital infusion to public sector banks.

But capital infusion and restructuring is part of the immediate solution. End of the day, if Indian public sector banks want to bring back soundness in their balance sheet, professionalism of the management and freedom from interferences from the government / politicians need to be ensured. Besides, the country needs to have systemic procedure for corporate bankruptcy. Otherwise, this pattern of formation of NPAs and rescuing the public secror banks with tax payers’ money becomes a scheme of cross-subsidization of the rich and mighty by the poor and is best avoidable.

*******

[1] Mohan, Rakesh and Partha Ray (2016): “India’s Financial Sector Reforms 2010-2016: Outcomes And Issues”, presentation at the 17th Annual conference on Indian economic policy, organized by the Stanford Center for International Development (SCID), Stanford University, available at http://scid.stanford.edu

[2] Several such measures were introduced. Illustratively, provisioning requirements for most standard assets reduced to a uniform level of 0.40 per cent and risk weights on banks’ exposures to certain sectors revised downward.

[3] RBI Press Release on “RBI introduces a ‘Scheme for Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets”, June 13, 2016; available at https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=37210

[4]http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/articleshow/52860383.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

[5] http://financialservices.gov.in/PressnoteIndardhanush.pdf