It may not be an exaggeration to say that excitement on crypto-currencies / crypto-assets of generation Y (or Z, may be) has not necessarily been shared by the global regulators, perhaps belonging to an earlier generation. Christine Lagarde, then Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) compared the “dizzying gyrations of crypto-assets such as Bitcoin” with the “tulip mania that swept Holland in the 17th century and the recent dot-com bubble”, and went on to say, “With more than 1,600 crypto-assets in circulation, it seems inevitable that many will not surviveia the process of creative destruction.”[1]

While the initial idea of crypto-currency perhaps dates back to 1998 when Wei Dai first discussed the idea of digital money named “B-money”, for all practical purpose its popularity / emergence can be traced since October 2008, when a presumed pseudonymous developer(s) Satoshi Nakamoto published a nine-page paper titled, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” (https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf).[2] In broad terms, a cryptocurrency is a virtual or digital money that takes the form of tokens or “coins.” The prefix “crypto” owes its origin to complicated cryptography that allows for the creation and processing of digital currencies and their transactions across decentralized systems. Primarily, cryptocurrencies are developed as code by teams who build in mechanisms for issuance (often through a process called “mining”) and other controls. Over the last five years Bitcoin price has increased more than 700 times; and there are at least 35 Bitcoin exchange markets where Bitcoin prices are quoted in standard currencies, each with the daily transaction volume above one million USD (Pichl and Kaizoji, 2019).[3]

Interestingly, while the ambit of crypto-currencies was confined to a relatively closed community till about 2016, since the beginning of 2017, the demand for crypto-currencies increased exponentially. Notwithstanding their popularity, regulators were somewhat cagey about their financial stability implications. Accordingly, different countries exhibited inhibitions of differing degrees. India was no exception. After an initial period of informal instructions, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), on April 6 2018, issued a circular prohibiting all commercial banks to deal with, what RBI termed as, “virtual currencies” (VCs). More recently, on March 4, 2020 the Supreme Court of India in a judgment quashed this RBI circular. Much excitement has been generated among the VC community about this judgement.

What has been the RBI rationale for prohibiting VCs? What has been the regulatory landscape in this regard? Will the Supreme Court judgment pave the way for VCs in India? This short note seeks to probe into some of these issues.

Towards a Cookbook on Cryptocurrency

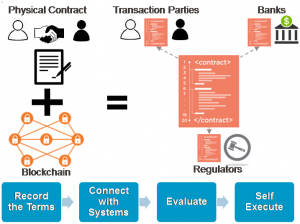

At the risk of appearing to write a cookbook, one needs to note that the origin of crypto-assets can be traced in blockchain, which is essentially “electronic ledger that records and verifies transactions made using crypto-assets”.[4] Bank of England in a submission to a Treasury Committee to the UK Parliament explained how blockchain emerged with crypto-assets:

“The innovations behind blockchain emerged from the initial cryptoasset, Bitcoin,…. Bitcoin was an attempt to build a payment system that did not rely on a trusted authority (such as a commercial or central bank) to maintain the record of payments and balances (the ‘ledger’). Importantly, anyone can participate in the validation of Bitcoin transactions—the network is ‘permissionless’ and its underlying blockchain (the database or ledger of transactions) is public. The Bitcoin network relies on multiple participants maintaining identical copies of the ledger and employs a process to come to consensus on the contents of, and updates to, this ledger.”[5]

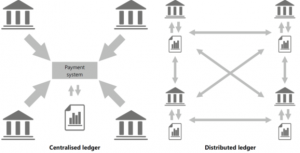

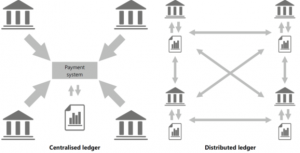

Thus, the crucial difference between bitcoin and a standard paper currency lies essentially in the backing of the centralized register in case of currency by the central bank.[6] The new system of Distributed ledger technology (DLT) is of key importance here (Figure 1).

| Figure 1: Distributed Ledger versus Centralized Ledger |

|

| Source: BIS Quarterly Review, September 2017. |

It is useful to refer to the research of Bank for International Settlement which puts it succinctly:

“DLT refers to “the protocols and supporting infrastructure that allow computers in different locations to propose and validate transactions and update records in a synchronised way across a network. The idea of a distributed ledger – a common record of activity that is shared across computers in different locations – is not new. Such ledgers are used by organisations (eg supermarket chains) that have branches or offices across a given country or across countries. However, in a traditional distributed database, a system administrator typically performs the key functions that are necessary to maintain consistency across the multiple copies of the ledger. The simplest way to do this is for the system administrator to maintain a master copy of the ledger which is periodically updated and shared with all network participants. By contrast, the new systems based on DLT, most notably Bitcoin and Ethereum, are designed to function without a trusted authority. Bitcoin maintains a distributed database in a decentralised way by using a consensus-based validation procedure and cryptographic signatures. In such systems, transactions are conducted in a peer-to-peer fashion and broadcast to the entire set of participants who work to validate them in batches known as “blocks”. Since the ledger of activity is organised into separate but connected blocks, this type of DLT is often referred to as “blockchain technology”. [7]

Volatility in the Exchange Rate of Cryptocurrency

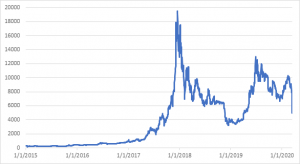

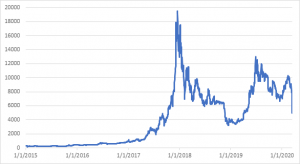

The exchange rate of Bitcoin exhibited huge volatility since the end of 2017 (Figure 2).[8] Pichl and Kaizoji (2019) highlighted the following traits of exchange rate of Bitcoin.

- The log return distribution of the Bitcoin exchange rate shows the fat tail covering the extreme event region of bubbles and crashes.

- The price of Bitcoin is highly volatile and not supported by “fundamentals” that is, any real economy in behind of cryptocurrency, and may have random walk (martingale) property.

- Arbitrage opportunities in the Bitcoin market cannot be ruled out.

| Figure 1: Exchange Rate of Coinbase Bitcoin (USD) |

|

| Source: Coinbase, Coinbase Bitcoin [CBBTCUSD], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CBBTCUSD, March 13, 2020. |

These features of exchange rates of cryptocurrency formed the basis of regulatory concerns.

Regulatory Oversight

Most of the regulators have shown concern about the unbridled growth of the cryptocurrencies. Very recently, in February 2020, Randal K. Quarles, Chairman of Financial Stability Board, mentioned, “Technology is changing the nature of traditional finance”.[9] Federal Reserve’s Chairman Jerome Powell described the rise of Libra project by Facebook as a “wake-up-call” for the regulators. During G20 Summit 2019 in Osaka, all the member countries had agreed to create a regulatory framework for cryptocurrency and crypto-assets following the standards set by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog.[10]

Over the past few years cryptocurrency became more systemically important, and have emerged as estate assets. In this environment as there is no agreed upon definition of cryptocurrency different countries have enacted different regulatory policies. Some countries like China have prohibited the use of any cryptocurrencies entirely and some countries (Example Switzerland and Venezuela) have embraced the idea of cryptocurrency to attract foreign investments, while the other have taken the “wait and watch policy”.

USA: In the United States, there is no separate regulatory framework for cryptocurrencies. Though cryptocurrencies are not legal tender in the United States, the trading activities are not entirely prohibited, though heavily monitored. They are regulated by different regulatory bodies under the existing legal framework. Currently, the Security and Exchange Commission (the SEC), the Commodity and Futures Trading Commission (the CFTC), the Federal Trade Commission (the FTC), and the Department of the Treasury regulate the cryptocurrency related activities. The digital assets and the tokens are considered as an “investment contract”. In 2019 The SEC also released a framework to determine when a digital token should be considered as securities.[11] A cryptocurrency exchange and the administrator who has the authority to issue and redeem the cryptocurrency is regulated by the Department of Treasury through the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network and prohibits any anonymous accounts. In 2019 a new legislation “Crypto-Currency Act of 2020” was brought into the congress aiming to create a robust regulatory framework with clear power and regulatory liability distinction.[12]

UK: Like the USA, the United Kingdom does not have any specific law to regulate the cryptocurrency. All the cryptocurrency-related activities are regulated through already existing law like Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, the Payment Services Regulation 2017, and Electronic Money Regulations 2011. The UK Crypto-assets Taskforce has defined cryptocurrency as “a cryptographically secured digital representation of value or contractual rights that uses some distributed ledger technology and can be transferred stored or traded electronically.”[13] Regulators in the country have been cautious about cryptocurrency regulations. Thought in the country, there is no blanket prohibition on activities related to cryptocurrencies, regulators have advised to restrain from cryptocurrency investments and warned about the risk involved through repetitive public notice.

Switzerland: Since the beginning, the position of the government of Switzerland has been encouraging for the cryptocurrency industry. The government of Switzerland is open to new development in this front. In December 2018, the Swiss Federal Council’s report on the regulatory framework for cryptocurrency had concluded that the existing laws provide a sufficient regulatory framework for cryptocurrencies.[14] On March 22, 2019, the Swiss Authorities proposed a new law to regulate the cryptocurrency. Currently, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) does not consider cryptocurrencies as security; instead, it is a “medium of exchange” and “storage of value.” Though trading involving cryptocurrencies constitute security, and those activities are regulated as normal trading activities like dealer license requirement, platform regulation, or prospectus requirements.

Singapore: Singapore is one of the most progressive countries in terms of regulation of cryptocurrency. Due to the regulators’ balanced approach towards cryptocurrencies, the cryptocurrency market is thriving. Cryptocurrencies are not regulated in Singapore through any legislation or by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS, the central bank of Singapore). In Singapore, cryptocurrencies are not considered as a means to store values; instead, they are recognised as assets and personal properties. Regulatory authorities encourage cryptocurrencies as “a mode of payment, and are a means of making payments.” However, some of the activities related to cryptocurrency are regulated as Securities by MAS. If cryptocurrency-related activities are classified as securities, then the parties engaging those activities are required to be registered. On 20 November 2019 MAS also proposed to allow payment token derivatives’ trade in Singapore.[15] The government and the monetary authority encourage this new distributed ledger technology. The MAS also has partnered with a private company R3 and a consortium of financial institutions to develop a payment platform using blockchain technology.[16]

Japan: Though the Government of Japan and the Bank of Japan do not recognise any cryptocurrency as security nor it treat it as “money,” Japan is one of the first countries to embrace cryptocurrencies. In February 2014, a Japanese company MTGOX Co, Ltd, started the cryptocurrency exchange services between the cryptocurrency and different legal tender. It quickly became the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange, and soon more business came into existence. With the booming business environment in the country, Japan was one of the first countries to regulate the cryptocurrencies and bring specific laws specific to cryptocurrencies. According to the law of Japan, cryptocurrency is a method of payment rather than currency. Cryptocurrency is defined as “proprietary value that may be used to pay an unspecified person the price of any goods purchased or borrowed or any services provided and which may be sold to or purchased from an unspecified person and that may be transferred using an electronic data processing system.”[17] To stop financial crimes, illegal trade, and terror financing, it mandatory for any services dealing with cryptocurrencies to register with the Financial Service Agency. Through different legislation, they have been empowered to regulate cryptocurrency-related services. Failing to register is a criminal offense for any entity or individual.

The Stance of the RBI

Indian Authorities do not consider cryptocurrency a legal tender or as a coin. Due to the lack of any regulatory norms, during the mid-2010s, businesses based on crypto-currencies grew. Trading volumes in the cryptocurrency markets reached as high as about $50 million to $60 million per day by the end of March 2018.

Different regulatory bodies in India, including the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) was somewhat uncomfortable with this development. Accordingly, in December 2013, RBI issued a warning to the general population about the risk involved in dealing with the cryptocurrency. Later in December 2016, in the financial stability report, RBI mentioned the establishment of a regulatory sandbox10 and innovation hubs to understand and support the development of new financial instruments and services. The report also highlighted the risk and concerns involving “virtual currencies,” the effectiveness of the monetary policy, and financial crimes.

On February 1, 2017, the RBI again issued a notice to the public about the usage and risks involved in using the cryptocurrencies. On July 25, 2017, an Inter-Disciplinary Committee released its report on the “virtual currencies” and the measures to regulate the “virtual currencies.” The report clearly distinguishes the distributed ledger technology and cryptocurrency. Inter-Disciplinary Committee recommended an explicit prohibition on the use, hold, and trade of any cryptocurrencies. The committee also recommended positively about the underlying distributed ledger technology and its potential usage “other than that of creating or trading in crypto-currencies.” On December 5, 2017, the RBI issued a notice iterating its concerns about the usage of cryptocurrencies.

Finally, the RBI in its Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies of April 5 2018, talked of ring-fencing regulated entities from virtual currencies and went on to say:

“… Virtual Currencies (VCs), also variously referred to as crypto currencies and crypto assets, raise concerns of consumer protection, market integrity and money laundering, among others. Reserve Bank has repeatedly cautioned users, holders and traders of virtual currencies, including Bitcoins, regarding various risks associated in dealing with such virtual currencies. In view of the associated risks, it has been decided that, with immediate effect, entities regulated by RBI shall not deal with or provide services to any individual or business entities dealing with or settling VCs.”[18]

Accordingly the next day, i.e., on April 6, 2018 the RBI issued a circular prohibiting all entities regulated by the RBI from dealing in Virtual Currencies (VCs). Specifically, the prohibition included “maintaining accounts, registering, trading, settling, clearing, giving loans against virtual tokens, accepting them as collateral, opening accounts of exchanges dealing with them and transfer / receipt of money in accounts relating to purchase/ sale of VCs”. [19] Regulated entities which already provided such services were asked to exit the relationship within the next three months.

Though the prohibition did not extend beyond the entities regulated by the RBI, due to lack of access to capital, banking infrastructure like maintaining the accounts, trading, payment settlement, or access to credit choked the new businesses dealing with crypto-currencies.

Later on, December 5, 2019, in the Monetary Policy Press Conference, to a question on RBI’s stance on cryptocurrency, RBI Governor categorically stated:

“…. With regard to digital currency, there are two aspects. One is private digital currency. RBI is very clearly against any kind of private digital currency. And let me also add that it is not RBI which is against it, world over, the central banks and the governments are against private digital currency. Because currency issuance is a sovereign function, it has to be done by the sovereign. A private currency cannot overwrite what is in the sovereign domain. And there are huge challenges with regard to money laundering and other aspects. With regard to digital currency to be issued by a central bank, that is central bank digital currency, this is very early. Some discussions are going on. The technology has also not yet fully evolved, it is still evolving. This is still in a very incipient stage of discussion and at the RBI, we have examined it internally. And we are continuing to have internal discussions. And we do have consultations and discussions with other central banks also. But it’s too early to talk about central bank digital currency. But as and when the technologically evolves, with adequate safeguards, I think it is an area which the Reserve Bank will certainly look at seriously, at an appropriate time.[20]

It is in this context that the Supreme Court judgement of March 4, 2020 assumes critical significance.

Supreme Court Judgement of March 4 2020

On 4 March 2020, the Supreme Court of India gave the verdict on RBI’s prohibition for financial institutions to deal with any entity engaging in the cryptocurrency-related activity.[21] In the verdict, the Apex Court told that RBI in some sense had violated Article 19(1)(g) of the Indian constitution, providing fundamental right to practice any profession. As the businesses involving cryptocurrency is not illegal in India, RBI cannot deny any business dealing with cryptocurrencies access to the formal financial infrastructure. In the verdict, the Apex Court has said the arguments made by RBI on financial crimes lacks empirical evidence and that RBI has not proposed any alternative measures to mitigate those risks, though, the judgment also acknowledged that this verdict based upon article 19 (1)(g) and does not cover any individual as stated in the verdict “Persons who engage in buying and selling virtual currencies, just as a matter of hobby cannot pitch their claim on Article 19(1)(g), for what is covered therein are only profession, occupation, trade or business.”

Interestingly, it was pointed out that that multiple reports both by RBI and Inter-Ministerial Group have given conclusive evidence that the distributed ledger technology and cryptocurrency are two separate entity, and call cryptocurrency as the “by-product” of the distributed ledger technology. The Apex court has also acknowledged after going through all the definitions a significant number of regulators that though “VCs are not recognized as legal tender,” “they are capable of performing some or most of the functions of real currency.” According to the verdict, money has three primary functions; “It provides, namely (1) a medium of exchange (2) a unit of account and (3) a store of value. Finally, a fourth function, namely that of being a final discharge of debt or standard of deferred payment, was also added”. Any cryptocurrency satisfies all but the fourth functionality, which is the conferment of the legal tender status by a Government/central authority. Thus, cryptocurrency satisfies the functionality of currency, and the Reserve Bank of India has authority over any cryptocurrency to regulate it. As per the Apex court, “the users and traders of virtual currencies carry on an activity that falls squarely within the purview of the Reserve Bank of India.” [22]

The verdict stated, “anything that may pose a threat to or have an impact on the financial system of the country can be regulated or prohibited by RBI, despite the said activity not forming part of the credit system or payment system.” Hence the verdict has strengthened the regulatory authority of the Reserve Bank of India, and in case of any legislative or executive actions on the ground of financial stability, the verdict will not hold. Thus, the verdict leaves room open for the proposed bill banning any activities related to cryptocurrencies in the parliament gets enacted into law and that will not violate any clause of the verdict nor it will be a violation of the fundamental rights of any individual under Article 19 (1)(g).

Way Ahead

While accepting the RBI’s jurisdiction over the cryptocurrency market, this Judgment could trigger a spurt of activity in this now moribund market. However, lot will depend on the regulatory and legislative action / reaction in this regard. The Government of India has already prepared a Draft of the “Banning of Cryptocurrency & Regulation of Official Digital Currency Bill, 2019” in August 2019. This Bill proposed to prohibit mining, holding, selling, trade, issuance, disposal or use of cryptocurrency in India.[23] While under the draft Bill, mining, holding, selling, issuing, transferring or use of cryptocurrency is punishable with a fine or imprisonment of up to 10 years, or both, there is a provision that the central government, in consultation with the RBI, may issue digital rupee as legal tender”. However, the government refrained from introducing the draft bill in the winter session of the parliament during November – December 2019. Going forward the future of cryptocurrency in India will depend upon a number of unknown unknowns. Illustratively, we do not know whether, in the days to come, cryptocurrencies could be replaced by Central Bank Digital Money. What would be interaction between the market participants and regulators / legislative actions? What stance would international bodies like G-20 or FATF is going to take? Future of cryptocurrency, like any other financial innovation, will lie in the outcome of such a cat and mouse game between the regulators and market players.

*******

[1] Lagarde, Christine (2018): “An Even-handed Approach to Crypto-Assets”, IMF Blog, available at https://blogs.imf.org/2018/04/16/an-even-handed-approach-to-crypto-assets/

[2] The actual cryptocurrency software was released in the open source domain in January 2009.

[3] Pichl, Lukas and Taisei Kaizoji (2019): “Volatility Analysis of Bitcoin Price Time Series”, Quantitative Finance and Economics, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321827427_Volatility_Analysis_of_Bitcoin_Price_Time_Series

[4] UK Parliament (2018): Crypto-assets, Twenty-Second Report of the House of Commons Treasury Committee, available at https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmtreasy/910/910.pdf

[5] UK Parliament (2018): Crypto-assets, Twenty-Second Report of the House of Commons Treasury Committee, available at https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmtreasy/910/910.pdf

[6] While over the years, number of other cryptocurrencies appeared, in terms of transactions bitcoin maintained its prime position in the cryptocurrency market. Ethereum (ETH); Ripple (XRP); Litecoin (LTC); Tether (USDT); Bitcoin Cash (BCH); Libra (LIBRA); or, Monero (XMR) all are examples of cryptocurrencies to name a few.

[7] Morten Bech and Rodney Garratt (2017): “Central bank cryptocurrencies”, BIS Quarterly Review, September 2017.

[8] Similar volatility is noticeable in other cryptocurrency market as well.

[9] FSB Chair’s letter to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors: February 2020

[10] Global Finance, G20 Osaka Leaders’ Declaration: 28-29 June 2019, available at https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/economy/g20_summit/osaka19/en/documents/final_g20_osaka_leaders_declaration.html

[11] Security Exchange Commission (the USA, 2019): “Framework for “Investment Contract” Analysis” available at: https://www.sec.gov/files/dlt-framework.pdf

[12] As per the draft bill there are three types of digital assets i) cryptocurrency ii) crypto-commodity (Goods and services with substantial fungibility) iii) crypto-securities (debt, equity and derivative instruments). The draft version of “Crypto-Currency Act 2020” available at: https://www.crowdfundinsider.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Draft-Crypto-Currency-Act-of-2020.pdf

[13] Cryptocurrency taskforce: Final Report available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/752070/cryptoassets_taskforce_final_report_final_web.pdf

[14] The Federal Council (Switzerland)(2018): “Legal Framework for distributed ledger technology and blockchain in Switzerland” available at: https://www3.unifr.ch/webnews/content/166/file/Attachments/Report%20Blockchain%20ICO.pdf

[15] Monetary Authority of Singapore (2019): “Proposed Regulatory Approach for Derivatives Contracts on Payment Tokens.” Available at: https://www.mas.gov.sg/-/media/MAS/News-and-Publications/Consultation-Papers/2019-Payment-Token-Derivatives/Consultation-Paper-on-Proposed-Regulatory-Approach-for-Derivatives-Contracts-on-Payment-Tokens.pdf

[16] Monetary Authority of Singapore (2019), Media Release, Available at: https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/media-releases/2016/mas-experimenting-with-blockchain-technology

[17] For more detail see: https://www.globallegalinsights.com/practice-areas/blockchain-laws-and-regulations/japan

[18] For more detail see: https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PressRelease/PDFs/PR264270719E5CB28249D7BCE07C5B3196C904.PDF

[19] These instructions are issued in exercise of powers conferred by section 35A (read with section 36(1)(a) of Banking Regulation Act, 1949), section 35A (read with section 36(1)(a)) and section 56 of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949, section 45JA and 45L of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 and Section 10(2) read with Section 18 of Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007.

[20] Available at https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/bs_viewcontent.aspx?Id=3798

[21] Two different petitioners went to court against this move: (a) the Internet and Mobile Association of India; and (b) a group of corporations that were in the business of running of crypto exchange platforms.

[22] The verdict by Supreme Court of India (2020) is available at: https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2018/19230/19230_2018_4_1501_21151_Judgement_04-Mar-2020.pdf

[23] As per this Draft Bill, cryptocurrency is defined as any information, code, or token which has a digital representation of value and has utility in a business activity, or acts as a store of value, or a unit of account.