Each year in April and October, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) comes up with two of its flagship publications, viz., the World Economic Outlook (WEO), and the Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR), coinciding with the Spring and the Annual Meetings of the IMF. While the WEO is a product of the Research Department of the IMF, the GFSR is coordinated by the Monetary and Capital Markets (MCM) Department. Often in the media attention on the WEO, the coverage of the GFSR gets somewhat lost, perhaps unjustifiably. The recent GFSR, which was published on October 18, 2019, is an outstanding report with rich analytical content as well as well-informed market perception. Spanning over seven chapters and covering issues as diverse as, global corporate vulnerabilities, institutional investors, emerging and frontier market, banks’ dollar funding, and sustainable finance, the report does justice both to the depth and the breadth of these issues. Many of these issues are beyond the scope of the current commentary. Instead, the present article looks into some fault lines of contemporary global financial stability, as revealed in the current GFSR.

Major Fault Lines

At the risk of presenting broad generalizations, a look at the current trends of global financial markets reveal the following six broad trends:

- In the backdrop of the US-China tariff war, there has been significant weakening of business sentiments.

- Coupled with technology and geopolitical tensions, such erosion of business sentiments have led to increases in policy uncertainty.

- This is perhaps best reflected in pronounced decline of long-term yield, which is largely seen as a leading indicator of a possible slowdown.

- However, the equity market has shown some sort of irrational exuberance despite the low business mood.

- The key to understanding the contradiction between the bond and equity markets can perhaps be traced in a shift toward “a more dovish monetary policy stance across the globe”. In particular, the futures markets tend to indicate that monetary policy rates are expected to be lower for “longer than anticipated at the beginning of the year”.

- There has been huge increases in debt stock and a significant portion of outstanding debt stock are at negative

While all these trends seem to have profound implications for global stability, in specific terms this commentary points out to three major traits of the current global financial condition, as highlighted in the GFSR.

Swings in Financial Markets

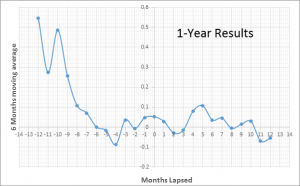

Global financial markets exhibited significant swings in recent period, reflecting interplay of two policy sources, viz., imposition of tariff on the part of the US on China, on the one hand, and the US monetary policy actions (both actions as well as intended), on the other (Chart 1). For example, there has been significant fall in global equity prices, after US President Trump’s speech of May 29, 2018 when he categorically mentioned, “China has consistently taken advantage of the American economy with practices that undermine fair and reciprocal trade” (Chart 1.1).[1] On the other hand, advanced economies governments’ bond yields of various maturities have experienced significant declines since October 2018. Of course, after converging to very low levels, in recent past there has been some increase (Chart 1.3).

In consonance with the gyrations in the financial markets, there has been substantial increase in volatility as reveled by movements in option-implied volatilities in the US Equity and Treasury Bond Markets (Chart 1.2). Finally, along with flattening (and in some case inverting) of the yield curves, the amount of bonds with negative yields has increased to about $15 trillion, “including more than $7 trillion in government bonds from large advanced economies, or 30 percent of the outstanding stock” (Chart 1.4).

Mr Powell versus Mr Trump: The Good Cop – Bad Cop Syndrome?

While the report is couched in the usual politically correct and conservative language of the IMF, there is a theme of the destabilizing effect of the tariff war and the stabilizing effect of the US monetary policy, running underneath the report. All actions / speeches of the US Fed Chairman have typically been followed up an upbeat mood in financial markets. Illustratively, after the US Fed Chairman, Mr Jerome Powell spoke on “Economic Outlook and Monetary Policy Review”, on June 25, 2019 at the Council on Foreign Relations, New York, the world equity prices increased significantly and volatility reduced. Interestingly, instead of announcing any tangible policy decisions, he went to say:

“We did not change the setting for our main policy tool ….but we did make significant changes in our policy statement. Since the beginning of the year, we had been taking a patient stance toward assessing the need for any policy change. We now state that the Committee will closely monitor the implications of incoming information for the economic outlook and will act as appropriate to sustain the expansion, with a strong labor market and inflation near its symmetric 2 percent objective”.[2]

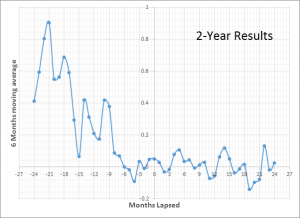

Does this mean the global uncertainties created by the trade and technology war between the US and China be countered solely by the arsenal of monetary policy? The answer at best is still couched in mystery. Interestingly, all the major central banks have adopted an easy money stance in 2019 (Chart 2). Significantly three major central banks, viz., Japan, Euro Area and Switzerland have negative policy rates; these are expected to continue at least for next three years. In some cases, the extent of negative interest rates has got accentuated. Illustratively, on September 12, 2019, the European Central Bank reduced the interest rate on its deposit facility by 10 basis points to (-) 0.50 per cent.[3]

Are the expectations from monetary policy too much? Can the negative effects of a trade war be countered by an overtly accommodative monetary policy? Does monetary policy has Atlas-like quality and has been condemned to hold up the celestial heavens for eternity? All these questions assume importance. In fact, a case in point is the recent spat between President Trump and Fed Chairman Powell. Reportedly, Mr. Trump called the US monetary policy “insane” and added that Mario Draghi, President of the European Central Bank, should take the helm instead (Financial Times, June 26, 2019).

| Chart 2: Actual and Expected Monetary Policy Rates in Advanced Countries (Percent) |

|

| E: Estimate

Source: Global Financial Stability Report, IMF, October 2019. |

Build-up of Financial Vulnerabilities

Accommodative monetary policy has its limitation. GFSR made a detailed sectoral and country-specific analysis of financial vulnerabilities and noted, “The prolonged period of accommodative financial conditions has pushed investors to search for yield, creating an environment conducive to a buildup of vulnerabilities.” Chart 1 below reports the financial vulnerabilities for six specific sectors, viz., banks, households, non-financial firms, Sovereigns, other non-bank financials, and insurers. Vulnerabilities of other non-bank financial entities seem to have increased since April 2019. In particular, among other nonbank financial entities, “vulnerabilities are high in 80 percent of economies with systemically important financial sectors, by GDP” and at a level that was attained during the global financial crisis. This could be due to an increase in leverage and credit exposures in the US and the Euro Area where institutional investors, in their quest for maximizing yield and targeted return, could have taken on riskier positions.

| Chart 1: Global Financial Vulnerabilities: Proportion of Systemically Important Economies with Elevated Vulnerabilities, by Sector |

|

| Source: Global Financial Stability Report, IMF, October 2019. |

Concluding Observations

One of the lessons from the global financial crisis is perhaps that vulnerabilities get built during good times. We do not know whether the current situation when the threats of trade war looms large, and bond yields have gone to very low levels (perhaps indicating global slowdown) can be termed as good times. But, the burdens of rising corporate debt, increasing holdings of riskier and more illiquid assets by institutional investors, and external borrowing by emerging and frontier market economies may not be nullified by accommodative monetary policy alone. All these are omens in the apparent exuberance in select segments of global financial markets. Thus, in some sense the GFSR seems to be cautiously pessimistic and warn us about the bad old days to come.

[1] The speech was followed by a re-imposition of a 25 percent tariff on all steel imports (except from Argentina, Australia, Brazil, and South Korea) and a 10 percent tariff on all aluminium imports (except from Argentina and Australia).

[2] Available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20190625a.htm

[3] The interest rate on the main refinancing operations and the rate on the marginal lending facility have, however, remained unchanged at their current levels of 0.00 per cent and 0.25 per cent, respectively.