Round Table

India Emerging: New Financial Architecture

Sankarshan Basu⃰

Finance & Accounting, Indian Institute of Management Bangalore, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

⃰Corresponding Author: E-mail: sankarshanb@iimb.ernet.in; Phone: +91 80 26993078

Short Title: India Emerging: New Financial Architecture

Keywords: New financial architecture; Integrated financial architecture; De-regulation; Global Financial Crisis 2007-2008; Banking; Mutual funds; Non-banking finance companies; Risk management

Abstract

The global financial crisis of 2007 – 2008 highlighted the need to re-evaluate several well established tenets in the world of finance. Questions have been raised the world over about the existing paradigm, leading to an acceptance that new financial architecture needed to be evolved and that new models need to emerge, keeping in mind the multiplicity of socio-economic realities that exist round the globe. In this context, the imperative for a new financial architecture in India is quite evident, and the ensuing panel discussion throws up some India-specific issues that need to be explored by the various stakeholders involved in this attempt.

Perspective note to round table

The global financial crisis of 2007 – 2008 has questioned many of the beliefs held very strongly in the world of finance, in particular about the way the whole system was developed and sustained. The collapse of most of the large financial institutions in the capitalist capital of the world, the United States of America, and the subsequent requirement of huge governmental support in bailing out these institutions to preserve the stability of the social structure has led to regulators (both national and international), policy makers, researchers as well as practitioners questioning the very model on which they had built their reputation, leading to an understanding of the requirement for a new financial architecture to be followed, going forward.

We are now at the point where the need for the new financial architecture has been more or less universally accepted, but the exact form of the same is yet to be understood and accepted. In fact, it is highly probable that there will be not just one model but multiple models depending on the underlying social fabric and requirements, and hopefully all of the models will coexist.

The financial architecture that has been in use was conceived in the wake of the Great Depression of 1929 and was designed to address the issues arising out the economic conditions at that point. Over the last 70 odd years, the economic conditions around the globe have significantly changed. The Second World War and the development assistance plans that were put in place post the war by the developed nations meant that there was an abundance of capital to rebuild the world. This also meant that a lot of the regulators’ frameworks put in place in the immediate aftermath of the Great Depression were slowly but steadily dismantled; so much so that by the 1990s the entire financial markets globally (particularly the developed world) were subject to very little regulation.

On the other hand, financial markets in countries like India and China were still significantly controlled by the regulators, and in some cases by the governments themselves. In the good years, through till about 2006 – 2007, this meant that the perceived benefit of deregulation that most of the developed markets saw did not really percolate to these markets and hence these markets had a persistent demand for larger levels of deregulation. This has been coupled with the need for relatively high growth rates that these countries would require to sustain their economies – a growth rate of 8% – 9% going forward for a number of years. One of the obvious fallouts of these kinds of needs would be the fact that the standard financial architecture that existed would not be able to sustain this level of growth – in fact no one segment of the financial sector will be able to sustain the growth required; hence the possible need for an integrated new financial order or architecture integrating the banking sector, the mutual funds, and the non–banking finance sector. Another sector that probably would need to be formally included in this new order would be the organisations that collate and provide all the relevant financial information – as, going forward, information will be the key driver and more so in the financial sector.

While the new financial architecture needs to be developed, each segment of the finance industry will be impacted. The banking segment will probably the most impacted as it is the largest contributor to the financial sector. The need for financial inclusion in the country, the push for the same from the government, as well as the additional responsibilities and requirements thrust on them on account of the various regulatory mechanisms, for example the Basel guidelines, will definitely make banking a whole new ball game when compared to the banking sector that we now know of. Implementation of and adherence to such requirements would also require significant amount of trained human capital and thus trained human capital would also form a pillar in the new financial architecture that is in the process of being developed.

The other major sector that probably has never got the attention due to it is the micro small and medium enterprises (MSME). It seems clear that these MSMEs are going to be the major drivers of growth in the future and hence the entire financial structure would have to give importance and prominence to the capital and fund requirements for such enterprises; this is particularly relevant given that the current share of the non–corporates in the Indian GDP is about 52% and is expected to grow in the coming years. The financial support needs to come from the formal banking sector as well as the non–formal sector represented by the non–banking financial companies (NBFCs). Interestingly NBFCs can also play a significant part in the financial inclusion of all citizens. In a sense, it is now clear that going forward, NBFCs will play an even larger role that it plays currently and such organisations will have to be given a place at the high table of finance on equal terms.

The other pillar of the new financial architecture will be the mutual fund industry. Globally it is already a very important player contributing around 36% of the global GDP. This number is only expected to increase with increased life expectancy and therefore an increase in the superannuated population leading to larger savings during the working life. On the contrary mutual funds contribute only about 7% to the Indian GDP; but as life expectancy increases, the retired population also increases, and thus the need for increased savings will become very important, and the mutual funds will be one of the prime vehicles of this investment going forward. The main driver that will lead to a successful increase in the increased investments in mutual funds will be improved and effective regulation of the capital markets, thereby increasing the confidence of the common investor in capital markets products and, as a consequence, the mutual funds.

The final pillar of this new financial architecture has to be information – information on all counts but in particular channelised towards risk management and risk mitigation. The same is being highlighted by all regulators – Basel guidelines by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) is a classic case in point. The importance is also growing as better and more efficient analytics tools are available today for users and regulators alike to carry out detailed predictive analysis and hence try and pre-empt adverse market moves. Even if the success of pre-emptive market moves may be questioned, the ability of these data based strategies will give all the stakeholders of the financial system a better chance to have more efficient and robust risk management systems – not that they will be successful all the time but the success rate will definitely improve significantly from the current times and thus improve the efficiency of the entire financial sector.

In this context, the imperative for a new financial architecture in India is evident. The following panel discussion, brings forth some of the issues that would need to be identified, particularly in the Indian case, as the regulators and the policy makers in conjunction with market participants, go about building a new architecture.

India Emerging: New Financial Architecture – Panel Discussion[1]

Chair: R Vaidyanathan

Professor, Finance & Control, Indian Institute of Management Bangalore

Panellists:

T Keshav Kumar, Chief General Manager, Commercial Banking, State Bank of Mysore

Imtaiyazur Rahman, Chief Financial Officer, UTI Mutual Fund

Sriram Ramnarayan, Country Head, Financial Markets, Thomson Reuters

- S. Sundararajan, Group Director, Shriram Group.

R Vaidyanathan

A new financial architecture is emerging in India. We are talking about 8-9% growth in the future. What are the challenges faced by the financial architects? What types of changes are required? To discuss these issues, we have experts from distinct areas — banking, mutual funds, non-bank finance, and risk management. We will have a short presentation from each of them pertaining to their domain, and then open up the discussion to the audience.

We have with us Keshav Kumar, Chief General Manager, State Bank of Mysore, from the area of Commercial Banking. He has been with State Bank of India (SBI) Project Finance, Mumbai, and was DGM Credit, at State Bank of Travancore, Kozhikode.

We have with us G. S. Sundararajan, Group Director of Shriram Group, the largest non-banking finance group in the country. He is the MD of Shriram Capital, the holding company of the group. The company is in the insurance business and financial services, both in India and abroad. As a group director, he is in-charge of subsidiaries, providing oversight in critical areas, primarily in strategic growth opportunities for the country.

We have with us Imtaiyazur Rahman, Chief Financial Officer, UTI. He also supports the global operation of the company and the private equity division of UTI. He has 27 years of experience in management and business leadership. He has been with UTI since 1988. He has served on the board of Invest India Micro Pension, collective investment as well as pension.

The final panellist is Sriram Ramnarayan, Financial Risk Division, Country Head, Thomson Reuters. He has been working in the finance sector for 18 years. Currently, he is the Mumbai Location Head at Thomson Reuters.

I invite Mr Keshav Kumar to speak first.

Keshav Kumar: Banks and the new financial architecture

The financial sector in India consists of commercial banks — private and public sector, foreign banks, all India financial institutions, and the non-banking finance companies (NBFCs). I will focus on banking and the changes required, the issues to be resolved in the formulation of the new financial architecture.

Banking has undergone a huge amount of change with the regulator playing his role in guiding the banks on the concepts of BASEL-1, 2 and 3, particularly on the need to maintain higher capital. Capital is an important element in strengthening the foundation of the bank and in building a healthy banking system. We need to ensure that we have enough capital to meet eventualities. This is an area that is going to be of greater prominence in the banking system. We cannot give loans just because there is an appetite for loans; we need to link loans to the capital that is available. Given that public sector banks are managed by the government with more than 51% shareholding, the ability to raise money is one of the main challenges. The government in its own way is trying to bring down the holding levels but this will take time. One of the structural changes that has to be made is for the government to move out, and retain only a controlling interest, leaving the professionals to run the show.

The next issue is streamlining the procedures and upgrading technology in banking. A lot of things have changed in Indian banking. When we got into the banking system in 1984, we had manual systems. As one among those who have gone through the process, I definitely know that we have come a long way. People with no experience in handling computers, who are retiring soon, have been managing systems successfully. The major issue that banks face today, which will impact their efficiency going forward, is that of human resources. Banks, at one point of time were able to attract the best of talent. It was the prime area where employment was being generated. Joining the bank as a probationary officer was not considered any less than joining the Indian Administrative Service. The salary structure was also similar at that point of time. But today, after the IT boom, the best of talent has not come to banks. This is the sector that is going to be very important for the economy. There has to be a distinct look at what needs to be done to attract the best of talent to banking, especially to the public sector. This is the most important part of the whole financial architecture that we are talking about. The challenge will come to a head in the next couple of years when the seniors in the bank retire – all those who joined in the late 70s and early 80s – and there will be a distinct gap in the middle and senior management levels. The seniors will be replaced by officers who have not had that experience. We have to take this challenge seriously and address it if we want banks to be the backbone of the industry and the economy.

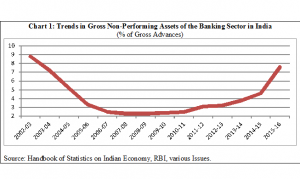

Coming to funding, we are talking about universal banking today, which has its own benefits and disbenefits. We started commercial banking from the short-term lending perspective of the industry and the all-India financial institutions took over the long-term funding of the industry. This created its own problems. Financial institutions did not possess the resources for asset liability management (ALM); they do not have the assets to match their liabilities. Banks moved into term lending and intra-lending. This has caused a major issue as the ALMs do not match. Our liabilities are of short duration whereas the assets needed to carry projects such as airport projects or port projects which are of10-15 year duration or longer, are different. Today, non-performing assets in the banking industry are causing issues. The prime reason for this is that we have not looked at economic length of the project or what the project requires but at a random number of 10-15 features based on ALMs.

We must have the ability to draw from long-term resources. In all other economies, these activities are funded by groups such as pension funds, Public Provident Fund (PPF), and so on through which more long-term funding is available but in our country there are several investment and regulation issues. Insurance companies only invest in AA or AAA rated companies. So when projects come up, they are unable to attract long-term funds and that is why they come to banks. When they come to banks, based on their ALMs, we give them loans for 10-15 years which impacts our profits. This is because such decisions are based on assumptions. A road project is assessed on what the traffic is going to be. These assumptions need not necessarily turn out to be true. You need a mechanism where we can viably assess such projects and change our goal posts. For that, you need ALMs on tenor-wise basis.

Going forward we need to have banks for varied interests and varied causes. A start has been made by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) with payment banks. A lot of disintermediation is happening and this is a great challenge. There was a time when banks were involved in various activities, now they find that they have to do clear credit activity. You need to see if income comes from non-interest income. In the past banks used to float funds. Today that option is not available in the banking sector. Going forward, we are going to have a layered structure where we will have specific activities given to different banks.

Next, we come to capital constraints and governmental compliance and regulatory compliance that banks have to meet. This is not a level playing field. Public sector banks have crucial social obligations. Public sector banks need to meet their social obligations, and at the same time focus on profitability as they are also accountable for their performance. The banks have to divert 40% of their lending to the priority sector. These are all social objectives. Unless there is a level playing field, you will not be able to judge which banks are doing better.

Information technology (IT) is already a challenge and given the stage that banks have reached, we are confident that the best of IT would come into this sector and we would be able to match the expectation of the customer. When it comes to IT, the objective of the bank will be to take its cues from the public depending upon their requirements.

Banking is in the cusp of change. It is a change which should happen and will happen. Going forward, we will witness various sets of banking improvements. The banking structure needs to be stronger so that it actually becomes the basis on which the economy works.

R Vaidyanathan

Thank you Mr. Kumar for initiating the discussion. Mr Kumar has identified the issue of capital adequately. He has also identified the huge gap that many banks face in terms of their age profile. Quite a number of people are going to retire because in the 1980s in the public sector banks, there was a slackening in the intake. This is a demographic problem in a number of banks. They have a junior level and then there is a huge gap. It is a huge challenge in public sector banks. Banks could leverage IT and overcome the circumstances.

The relation between the government and banks is an age-old issue in India. The government pressure on banks to meet the public obligations and priority sector is phenomenal. All the banks face this.

We will now have perspectives from the non-banking sector which occupies a very large space in the Indian context. I request Mr Sundararajan to highlight some of the issues in that space.

- S. Sundararajan: Challenges faced by non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) in India

I am going to focus largely on the Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) space, the role that non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) play and how they are or are not facilitated within the regulatory framework; also, what needs to be done in the new financial architecture to ensure that the NBFCs are supported to give credit to MSMEs in a big way, which alone will ensure that we have a sustained GDP growth of 8% or above.

Medium enterprises have a reasonable amount of credit which comes in from the banking sector. Micro and small enterprises are largely unorganised, but they do not like to be called so; they call themselves self-organised. Many of them are not registered. They receive credit from local cooperatives which are often private co-operatives. Some NBFCs have taken the risk over the years to lend to micro and small enterprises, and see that they grow, which has had a multiplier effect in terms of positively developing the community around them. In terms of financing, every bank says it lends to MSMEs. One would think that MSMEs are the most “overbanked” sector, but they are actually the most under-served. The MSMEs rarely get the credit they need for their growth from banks. So MSMEs are largely served by the NBFCs.

Financial inclusion is a term that has been heard for the last few years, but much more today than before. It is something that some NBFCs have been doing very significantly and they have been niche players in transport finance, equipment finance, small business finance and so on.

The primary challenge faced by the regulators with regard to NBFCs is that that today, of the 12,000 or so NBFCs which are registered with the RBI, only about 20-25 of them account for about 70% of the lending in the marketplace. Many of the other players are either inactive or do small business in their local area. The regulator has a lot more focus when it comes to regulating banks (public deposits are a big concern for regulators and they have to protect the depositors), and NBFCs have been regulated with a very light touch for the first 15-20 years. However, over the last 7-8 years, the regulator has looked at NBFCs with more focussed attention.

The thought process now seems that as in the global environment, NBFCs and banks should have a level playing field. Therefore, NBFCs should be regulated just as banks. Some regulations have come about over the last few years, especially in the last one and half years which I believe are going to have an adverse impact on how NBFCs lend to micro and small enterprises. Perhaps this is why in the last budget announcement, there was a separate committee set up to examine the financial architecture of the MSME sector under K V Kamath[2].

The issue here is that if NFBCs are regulated the way banks are, be it in terms of capital adequacy norms or provisioning norms or anything that affects the advances made by NBFCs, then NBFCs will also target the same customers as banks. Today if there is any financial inclusion happening (when I say financial inclusion I am not focussing on savings bank accounts or insurance, I am focussing primarily on the amount of credit available from the organised institutions to the sector which is deprived of credit) it is through the NBFCs. There is a lot of mutual exclusivity between the target markets serviced by banks and by NBFCs. Further, there is a significantly higher level of risk which is being taken by the NBFCs because they have light touch regulations and they are allowed to take this risk. On the other hand, banks depend a lot on public deposits for their funding, so the RBI regulates banks more closely. Today, banking is a low risk-low reward business. While there may be no bank which has more than 12% return on equity (ROE), banks have a premium in terms of their valuations, they have a lot of investor interest and the overhang of RBI control and regulations is seen as a safe bet in the financial services space.

In the case of NBFCs, because of the light regulations and some errant players who have misbehaved in the market place, the RBI has decided to regulate all the NBFCs in the format of the “lowest common denominator”. They have decided to regulate the entire NBFC sector in the light of the few failures and with a view to preventing further failures, which has made life much more difficult for these 20-25 NBFCs who are the only ones catering to micro and small enterprises. According to the committees advising the finance ministry, unless we have a separate architecture created for small business financing, financial inclusion will continue to remain a dream; and even the few finance companies which are doing good business will cease to exist. Even if banks start understanding these customer segments, and try to serve them in an effective way, it will take another 15-20 years for them to be effective. Till then, we need NBFCs to flourish continuously and grow. There is a lot of appreciation for the role played by NBFCs from the finance ministry. We are confident that there will be significant changes and some amount of facilitation will happen which will enable NBFCs to continue the process of growing and giving more credit to the micro industries.

To give you a brief background on the character of MSMEs, though they are clubbed in one department and under one acronym, there is a lot of difference in terms of their characteristics. Medium enterprises typically have beyond INR 20-25 crores of turnover. They typically need multiple bank products and they have grown in different sectors of the Indian economy. Their risk is perceived to be relatively lower than the micro and small industries. They are registered companies, some of them are even limited companies. Therefore there is a lot of transparency and their financial documents are available because of which banks have a certain comfort level with them. None of this exists with most of the micro and small enterprises. At the same time, most micro and small enterprises at the lower end do not need any product other than term loans; they have enough collateral available which they are willing to give against loans. Today, when they take loans from NBFCs or local money lenders, their interest rates are much higher. The interest rates are more because there are very few players in this segment and the supply is much lower than the demand. Also there is a perceived high risk on the part of RBI and other players who are in this space. Therefore, there is a higher return which is seen and made available to NBFCs.

The objective of the new architecture for small business finance is to ensure that more and more players come into the open. If more entrepreneurs come into the MSME space the ultimate pricing for these customers will come down, and there will be more inclination to borrow from NBFCs, and therefore there is huge growth opportunity and potential which will be realised as we go along. It is extremely critical and imperative for NBFCs to grow and we hope the new architecture will facilitate this. In the last few years we have seen a lot of regulations coming in, but this has not stopped the NBFC sector from growing. NBFCs have been fighting for survival all along and they know the art of surviving in the most adverse conditions. The new financial architecture is critical to enable NBFCs to play an even more significant role in financial inclusion in the country.

- Vaidyanathan

Thank you Mr Sundararajan for an excellent exposition on the issues faced by NBFCs. Though little recognised, NBFCs play a very large role in our economy. This segment includes money lenders and the bigger companies. Of the 58 million small enterprises in the country, most of them are non-corporate. But in a district survey, I found that most of management research is only concerned with corporates. In terms of value addition, the non-corporates constitute around 50% of the GDP, while corporates constitute only 12-13%, but we are all enthusiastic about corporates. NBFCs perform a phenomenally good role in terms of reaching the last man. The usual complaint is that they charge a very high rate of interest but funds are otherwise not available to the average person. It is not so much a rate of interest issue but a question of availability and with the least amount of paper work. Much of these transactions are based on relationship and trust.

There is a general opinion that gold is most unproductive. We do not realise that gold is the single largest collateral in the country today for small businesses. I have a flower vendor near my house. There are times when she wears bangles and times when she doesn’t. When she doesn’t have bangles, the business is down. She would have mortgaged the bangles for working capital. When the business is doing well, the bangles come back. So, gold is not an idle asset. It is one of the largest collateralised items in this country, and that is why gold will occupy an important place. We hope the new financial architecture will factor that in.

We now have Mr Rahman from UTI. He will talk about mutual fund investments and their issues.

Imtaiyazur Rahman: Mutual funds — issues and developments

We will take a few minutes to look at the global perspective of mutual funds and then deal with the Indian mutual fund. So far as global asset managers are concerned, it is a very rich sector. Global asset managers manage the total assets (TA); they manage the traditional mutual funds and also manage the alternative assets, globally.

According to a study, global assets under management (AUM) was $67 trillion (TD) last year. In 2020, it will reach 100 TD. What are the segments that are going to contribute to it? The traditional mutual fund in 2012 was around 65 TD. In 2020 it will go up by 40 TD. The mandated assets in 2012 was 31 TD and that will go up to 47 TD in 2020. Alternatively, private equity was 7 TD; in 2020, it will be 13 TD. There are four broad factors which will drive AUM. In most of the Western countries, there is an ageing population. So they will save more towards retirement benefits. There will be serious shift in the culture of investment in the emerging countries. The culture of saving will move towards investment. High net worth individuals (HNI) will accumulate more wealth by way of ESOPs, creating more organisations, and new entrepreneurs. Financial literacy is going up in a big way and all these factors will lead to 100 TD assets. These assets will help the industry and economy to grow, and to meet growing capital requirements.

It is important for us to see the Indian mutual fund industry in three different perspectives. In 1963-64, the Government of India (GoI) started the Unit Trust of India (UTI), which dominated the scene until 1987. In 1987, GoI decided to open up this sector and it was available to public sector undertakings. Many public sector banks like Canara Bank and SBI started their own mutual funds. Before 1987, UTI had Rs 4700 crores of AUM. When the sector opened up in 1987, the AUM rose to Rs 47,000 crore. In 1993, when this sector opened completely to the entire public sector, AUM has grown from 47,000 crore to over Rs. 10 lakh crores. But, here we have to introspect. What is the contribution of MF? The allocation of household savings to MF is 3%. Mutual fund in India contributes only 7% of the GDP while global MF contributes 36% of the GDP.

Where does the money go? Bank deposits account for 56% and this trend continues. The allocation to MF is far less. We need to introspect on this growth. Compare 2009 and 2014. In 2009, the investment of corporate holdings in MF was 51%, HNI had 22%, and retail had 21%. This has shifted. In 2014 corporates hold 50% in MF, HNI has gone up from 22 to 27% and retail continues to be at 21%.

There are three important matrices we need to look at. First of all, the investor-mix. There is a lot of concentration as far as the corporate sector is concerned. Other statistics show that there is a large concentration as far as cities are concerned. The top five cities of the country contribute 74% of the ADR and Bangalore is one of them. Next top 10 cities contribute 14%, 88% contribution comes from top 15 cities. Only 12% of the money comes from beyond the top 15 cities. So, we are seeing high concentration in cities as well as the corporate sector. Coming to the third matrix, income funds constitute 56% of the ADR, liquid funds 13%, and equity funds 21% of ADR. This is the latest trend.

By 2020-25, MF will have 10% share in household savings. If this is the goal, what are the things we need to do? Basically, there are four drivers in this industry; one is Product and the other is Customer. There are two types of customers: distributor as a customer and the industry as a customer. The other drivers are Operations and Regulations. If we need to achieve our investment goal, there needs to be a serious shift in the minds of the people from savings to investment.

As asset managers of MF, we need to play the right role, i.e., we need to come out with the right product. If we look at today’s market, it is really crowded. All of us come out with the same product. Equity funds – large cap – there are 40 large caps in the market. And there is no great differentiation. So we need to launch a product that is relevant, we need to price it well and position it well. Coming to the investor mix, there is high concentration geographically as well as in terms of the participants. We need to diversify quickly.

In the last 7-8 years, there has been a huge amount of investment by the MF industry, including the regulators, in investor education. But it is very fragmented. So we as an industry need to work very hard and ensure that new investors are inducted. The number of folios for investors is only 4 crores. It has not grown. We can see some growth in equity fund only in this financial year. But again if you look at the flow, it is worrisome; Rs 95,000 crore has come in the last 8 months and Rs 55,000 has gone. This is a trend.

The MF industry needs to change its landscape and from mid-MF player, it should become the asset manager. While managing assets, the MF industry players also need to manage the pension fund, insurance and the money in alternative spheres. Only then can we achieve the goal of 10% MF share in household savings.

The next important piece is distribution. The MF industry is heavily dependent upon distribution. We have five different channel partners. Banks have the largest dominance in the top tier cities; independent financial advisors (IFAs) are found across the country; we have national distributors and regional distributors. Apart from the three parties – investors, distributors, and asset managers, there is also the regulator. And in the distribution space their interests are not aligned. The regulator is saying you can’t pay so much of commission. The worry for the small MF player is that the large players have deep pockets and will pay more commission and will take away the entire space. The large player says X has large number of equity elements, we have smaller number of equity elements, so we must buy.

Periodically, there used to be a huge problem in this space. UTI had over 150,000 IFA distributors. Then, there came a regulation that they had to be American National Standards Institute (ANSI)-certified. The number got reduced substantively. Now, there are 60,000 IFAs, and out of them only 5,000 are active. This is worrisome. What we need to do is make sure a new generation of IFAs comes in and they are paid well.

The last important piece in the MF industry is the regulator involvement. This industry is highly regulated. We are required to produce several documents. But there is some welcome development from the regulator side as well. The regulator came out with the provision that the paid up net worth of asset management needs to be Rs 50 crore. The regulator wanted to send out a message that only serious players will be encouraged here. They increased the capital adequacy requirements from Rs 10 crore to Rs 20 crores. They wanted the asset managers to put their skin into the system and therefore we at UTI are required to invest in all open-ended schemes equivalent to 1% of AUM or Rs 50 Lakhs, whichever is less. This is really welcome. But many of the incentives are non-tax. If this industry has to grow, we need to get a lot of tax benefits from the Government of India. There has to be necessary provision in the law that MF should be given this benefit.

In conclusion, I would say MF needs to be permitted to become the asset manager for insurance and pension funds. Mutual fund needs to have a large distribution base and the number of regulations needs to be reduced. In this entire space, digital strategy is crucial, and is going to be a big game changer. The better the digital strategy, the lower the cost, and the better the efficiency. With more digitisation and IT initiative, we will be able to serve the customer better.

- Vaidyanathan

Thank you Mr. Rahman for highlighting the achievements as well as the travails of the MF industry – 10% of the financial savings going into the MF industry will be a very positive development. As of now, the bank is the most preferred destination for household savings not only in India but all over Asia because the capital market is not much trusted by the household saver. We also hope that the regulatory framework would be much more favourable. Perhaps the developmental role of the regulator should be stressed. The perception of the regulatory authority or regulation should change.

I would now like Mr Sriram to consolidate the whole issue based upon his experience, including the risk management perspective.

Sriram Ramnarayan: The risk management perspective

Going by the presentations of the earlier speakers, everyone is talking in terms of growth in the banking sector. None of us is complaining about regulations, as such. All the presentations spoke about how inevitable growth is and how can we ease the bottlenecks and enable mechanisms to grow faster.

To give an example from the treasury space, ten years ago I was in risk management. At that time, you used to be very happy in the banking and financial sector, if you had a treasury recapture and position keeping system in your books, mainly in forex which runs into billions and billions of dollars on a day-to-day basis. If you could electronically capture the deal, pass it onto mid office and to the back office electronically, untouched by human hand, you were stated to have implemented a risk management framework for your organisation. People would put it in their balance sheets, if you can recall, that they were proud to implement so and so risk management systems in the organisation. This was what risk management constituted 10 years ago.

Today, risk management has taken a completely different hue for the simple reason that most of the trading is done at such a fast pace, and it is governed by things completely beyond your control. If you are aware of the things that are behind that change and the change in trading mechanism, you must be lucky. Therefore, one of the prudent ways to look at the framework for risk management in order to facilitate all the businesses that you want to grow, is to try and put all the processes for known risks together. Unknown risks, you cannot combat. If someone says they have a comprehensive risk management framework or a complete risk operational system, that is a doubtful claim.

For example, if you look at the way equities are trading in most parts or the algo trading or machine trading mechanism that is happening now, 80-90% of the global trading is done by machine. Those machines have a vast amount of historical data built into them comprising simulation, analysis of last 15 years, data of a particular country, climate, political influence, and so on. People used to take a look at the news and past credit and make their decision. Today, the machine does that in a micro second or even a nano second. What do these machines do? They simply take all the historical data, look at all news on BBC or Reuters or Bloomberg that comes in electronic format, read that news, and relate that news to similar events that took place 5 or 10 years ago. They look at questions such as: How has the market responded? What is the market sentiment, the reaction with respect to such a response? What will be the reaction once such news is out in the market? Which way will the market move? The machines provide a positive or a negative sentiment and then ask “Do you want to trade?” This is a question pertaining to trade in millions of dollars — yes or no? The order is executed in less than a micro second. Before we as human beings can see that news on the machine, the order is already executed between the two extremes.

You need to have good risk management processes in place in order to address those individual applications and markets. It is again a myth when people say they need to have a comprehensive risk management solution that takes care of everything and all the activities of a bank or a financial institution. Such a solution does not exist. If you look at the treasury risk management system, it is so different from the core banking system where the emphasis is on credit. Each bank knows exactly what credit model is best for it. An external credit rating agency can only do so much. The real estimate of the credit risk is done by the person who takes the decision. I have been saying this at various forums – the last man who takes the risks when he gives a loan knows what the probability is of the loan being returned. Similarly, in infrastructure funding or the trading environment where the trader hits the buy button on the screen and says buy 5 million, he knows in his heart what exactly the impact of his actions could be on the organisation, and collectively five such people know what is the impact of such action is on the state of the economy, which will contribute to systemic change. The herd mentality of five people going in the same direction or going wrong contributes to a systemic risk.

Having said that, what is the new risk management principle? What are people now looking at? I spoke to a compliance officer of one of the big MNC banks recently who said that one of his big worries was how he did risk management. The organisation had all systems in place. The department heads in the organisation had to tick mark on a form that they had complied with all processes. But the compliance officer could not be sure because he was depending on someone else’s tick mark. Therefore, people are now looking at various processes by which you can capture all the risk, the birth place of those risks and bring them all under one operational framework so that they could be in a position to see the risk. How much you act on that risk, how much you cover is entirely up to you. For example, if you go to the World-Check database[3] the UN gives a list of about 1000 people you should not trade with. If you go to a software company/service provider, they will give you 1,50,000 names you should not deal with. However, these are not blocked deals, they are cautions provided by the service provider. The risk culture is changing due to the very complex business environment. The man on the floor – the man at the end of the cycle where you disburse money in trade – that is where the risk culture has to come from and has to go all the way up to the board. This is the reason why in the New Companies Act, the responsibility is placed on the CFO and at the same time, you have the CRO and the internal auditor who is responsible and answerable to the board.

Having said that, who is most apprehensive about all these regulations? The board of directors. Now, the board of directors is telling us – please equip us to be aware of what is going on, as independent directors in the company. Is there awareness among them? Are the independent directors capable and do they have the time and wherewithal to read the reams of paper they receive and come back with recommendations and decisions points? Physically it is not possible. So, now the board is focussing on how to train the independent directors to have a bigger perspective, of being able to see what others cannot. That is what risk management is about.

Compliance is another big question in people’s minds. Indian companies are investing all over the world. They are subject to so many compliance laws that the investment and returns expected by investors overseas and in India can be wiped out by one penalty fine. So, the dire need for people is to see, in one place, the compliance laws that they are supposed to adhere to. Even in India, different states have different labour laws, laws with respect to doing business, local taxes, octroi, and so on. The entire framework of risk, governance and compliance now has to take a unified shape and form which is addressed by systems, and by people, most importantly, by people with expertise. You cannot lose people who understand the business. You need people who understand and implement the processes and you need the risk culture to be propagated across the organisation.

I would like to leave the audience with one thought. We have several regulators — insurance regulators, financial regulators, forward market commissions, SEBI, RBI, and IRDA. Is there a need to have a wrapper of a regulator? Do you need a unified system in the country as a whole to ensure that the financial systemic exposure is better controlled? Do you need linking between regulators? Do you need a unified regulator who has overall view on at least certain basic principal parameters which then can then boil down to industry-level specifics? The question cannot be answered in a day but it is a thought process for all of us.

- Vaidyanathan

Thank you for bringing out this important issue of role of directors. The recent 2013 Companies Act is, in a sense, a draconian act; several independent directors are quitting directorships and companies are desperately in search of good directors.

What the system has done in its enthusiasm is practically make the independent director more responsible for the affairs of the company than the executive director. They have made conditions very stringent; in a few years, many companies, particularly listed ones, will find it very difficult to get people.

We always have pendulum swings from one extreme to the other. That seems to be the Indian perspective. At one time the entire system was an outcry system, then it became 100% software system. No via media. There should be a re-look at it if you want capable people on the board who have to provide some amount of advice. The second important point concerns the time duration for decision making. The time perspective should be commonly understood across the board.

We will now open up the discussion to the audience.

Discussion

Q: My question is to Mr Sriram. You mentioned that 80% of the global trading that occurs is electronic in nature. As part of the research at IIMB, we found that the space in India is limited to between 30% and 40%. How aggressive is that space going to be in the coming years?

Sriram Ramnarayan: In India, it is a different scenario in terms of the percentages. But we see that in India, it is growing up slowly, thanks to our regulators and in some manner, the machines. The most important requirement, other than getting the programme, the system or the risks and controls right, is availability of technological infrastructure to such a degree that you are able to rule out any glitches in order to execute your trade once you are sure about your machine tradable capability. I think electronic trading is coming and is unavoidable; but whether it is coming in a big way, and the speed of the change, is something that one needs to see; it is difficult to predict.

Imtaiyazur Rahman: To supplement what Sriram said, SEBI has now allowed direct market access. So, now most of the participants are going directly to the market instead of going through the broker. I think this is the beginning but going from 50% to 80% will not take much time; going from 40% to 50% may take some time. Once it crosses 50%, reaching 80% will not take much time.

Q: I want ask you a question on the human resource policy of public sector undertaking (PSU) banks. I recently conducted a 3-day programme on financial derivatives in the Staff Training College of a major PSU bank. Half the participants were in the age group of 58-60 years and they admitted that there was little incentive for them to learn complicated subjects at that stage. At another such programme, there was a very bright young participant who was very good in treasury risk management and absorbed everything we conveyed. But a year later he was transferred to a rural branch of the bank and he had to sell agricultural loans to farmers when he has absolutely no talent for it. Why do banks have these kinds of policies?

Keshav Kumar: Coming to the age factor, as I said in my presentation, post 1987-88, the recruitment of officers was totally stopped in PSU banks. There were no new people brought in through the bank recruitments for 10 years. Post 2005-06, more recruitments are taking place and you will see younger faces sitting in the banks. This is an ongoing process.

I also mentioned in my presentation that structured and varied banking is coming in where different sets of banks are assigned different sets of practices. At present banks are doing all kinds of activities at the same time. We are told by government that we have to give priority loans, and so on. There is a major regulatory issue there. The regulations affect all aspects such as recruitment, credit and risk taking. There is a certain mindset that is part of the Indian ethos, especially in earlier times, and I am confident that it is changing and will change for the better.

Q: It is true that when some untoward incidents happen, the regulator starts tightening the belt. However, in the larger perspective of the protection of interests of the general public, how would you take care of such things if these types of regulations were not there? An example from the recent past of companies that have garnered huge amounts of money is the Sarada Group in West Bengal, and the Sahara Group. If you don’t bring in regulations, how will you ensure control?

- S. Sundararajan: Where you have people squandering public money, there should be action taken. However, unless it is systemic, you cannot have regulatory changes. If it is sporadic, you have to address it the way sporadic issues are addressed. For example, Sarada was just a corporate collecting deposits. They were not authorised to collect deposits. The moment they got caught, they were labelled as a chit fund company. They were not a chit fund company. If you are a chit fund company, you have to be registered with the chit fund registry.

Sporadic changes cannot have a regulatory undertone. When you apply the rule of the lowest common denominator, it will not facilitate people who are doing well to continue to grow well and contribute to the economy. That is something which needs a mindset change with the RBI and other regulators.

Q: This is regarding the volume of automatic trading in India. The SEBI regulations in the last few years are mainly about having an empanelled auditor and other aspects. What is the next thing? In Europe and in the US they are coming up with more regulations. Are the brokers providing the right platform for the customers? Do you see that coming in future in India?

Imtaiyazur Rahman: This is a real concern for me as a mutual fund asset manager. Let me give you an example. A few years ago UTI was trying to have a strategic alliance with another company. I met a couple of their broker dealers. Whenever they have to meet a client, they have all the records with them. They record each and every discussion including discussions of their clients’ expectations, their age groups, their net worth, what they want to do and how much they want to invest. There was a very open dialogue between investor and the broker-dealer. That is not there in our case. The lack of financial literacy is one of the primary reasons for this.

Mr Sundararajan mentioned the chit fund. I come from the state of Bihar, from a village. Whenever I go to the village and speak about mutual fund, the only question I am asked is about the returns. Chit fund offers them 16% returns. Mutual fund cannot offer any assured returns; therefore financial literacy is very important.

When IFAs, who would be selling the products of the top few asset management companies (AMC), interact with the people in the village, the only question the investor asks is where he has to put his signature. There needs to be serious shift about financial literacy. People need to take control of their own money. Unless that comes, it will be very difficult. No matter what regulations you put in place, we will not be in a position to avoid this. So, here, it is not really a bread and butter income for the IFA. They do it as a side income. My sense is unless we all grow, all four of us – bankers, insurance companies, NBFCs, IFAs, and educate the people enmasse, we will not be able to see real light of day.

Sriram Ramnarayan: The other side of the picture is the institutional trading. How much will you practice? How will the regulation work? It is a question of give and take. I do not think even locally in India, institutional players are eager and keen to increase themselves 10-fold because they are aware of the risks to themselves in the architecture that goes into the delivery of such a mechanism. So, as Mr. Rahman said, there will be growth, but the pace of growth will be dictated more by the market conditions and risk mitigation mechanisms rather than the regulators themselves.

- Vaidyanathan: Thank you all very much. We have had interesting perspectives from different dimensions of the financial market. I would like, individually, to thank Sriram, Rahman, Sundararajan and Kumar.

[1] The panel discussion was part of the 4th India Finance Conference 2014, December 17 – 19, 2014. This part of the article carries edited excerpts of the presentations made at the panel discussion. The views expressed by the panellists are personal and academic in nature and not necessarily the views of their organisations. The presentations of the panellists were made in an academic context in an academic institution. The data and statistics are as quoted by the panellists in their presentations.

[2] This committee has submitted its report in February 2015. http://msme.gov.in/WriteReadData/DocumentFile/2015_02_MSME_Committee_report_Feb_2015.pdf

[3] a database of Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs) and heightened risk individuals and organisations which is used around the world to help to identify and manage financial, regulatory and reputational risk.